Tylor 1871 Culture as ââåthat Complex Whole Which Includes Knowledge Belief Art Morals Law

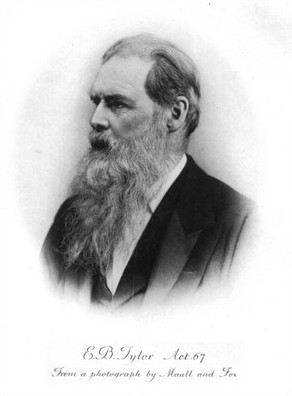

Figure 1: Engraving of Edward Burnett Tylor

Edward B. Tylor (1832-1917) established the theoretical principles of Victorian anthropology, in Archaic Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom (1871), past adapting evolutionary theory to the study of human club. Written at the same fourth dimension as Matthew Arnold'due south Culture and Anarchy (1869), Tylor defined culture in very different terms: "Civilisation or culture, taken in its broad ethnographic sense, is that circuitous whole which includes knowledge, belief, fine art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society" (i: one). Hither culture refers to the learned attributes of society, something we already take. Arnold's theory focused instead on the learned qualities that we should have, which he prescribed every bit a way to improve the existing society. (See Peter Melville Logan, "On Culture: Matthew Arnold'due south Culture and Chaos, 1869.″) The prescriptive chemical element of his theory thus was antithetical to anthropology'due south descriptive premises. Nonetheless, the simultaneous appearance of the two new theories of culture suggests a connection between them, and in fact both versions of "culture" had an overlapping involvement in responding to i and the same problem. Each redefined culture from a term express to individuals to 1 that encompassed society as a whole. While Tylor focused on the insular, subjective life of "primitives," Arnold thought that Victorians displayed a like incapacity. Yet the axiomatic differences betwixt Arnold's treatise on Victorian Uk and Tylor's on human prehistory, both works focus on the trouble of overcoming a narrow subjectivism and learning to comprehend the social trunk as a whole. The two were thus more alike than not, representing dissimilar approaches to the same trouble, rather than ii unrelated uses of the term civilization (run into Stocking, "Matthew Arnold").

For Tylor, Anthropology was a "science of culture," a system for analyzing existing elements of human being civilization that are socially created rather than biologically inherited. His piece of work was critical to the recognition of anthropology as a distinct branch of science in 1884, when the British Clan for the Advancement of Scientific discipline admitted information technology equally a major branch, or section, of the lodge, rather than a subset of biology, as had previously been the case. Tyler was the first president of the department, and in 1896 became Professor of Anthropology at Oxford, the start bookish chair in the new discipline (Stocking, Victorian Anthropology 156-64).

While a foundational figure in cultural anthropology, Tylor idea about culture in radically unlike terms than we do today. He accustomed the premise that all societies develop in the same manner and insisted on the universal progression of human civilization from savage to barbarian to civilized. Nowhere in his writing does the plural "cultures" announced. In his view, culture is synonymous with culture, rather than something particular to unique societies, and, so, his definition refers to "Culture or culture." In part, his universalist view stemmed from his Quaker upbringing, which upheld the value of a universal humanity, and indeed Tylor's refusal to have the concept of race equally scientifically significant in the study of culture was unusual in Victorian science.

The biology of evolution was explained by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species (1859), and he expanded his finding to include human development in The Descent of Man (1871), which was published the same twelvemonth equally Archaic Culture. While Darwin concentrated on biology, Tylor focused solely on the development of human culture. In this, he participated in a lengthy philosophical tradition explaining human evolution from its beginning to the present day. This speculative practice extends back to classical antiquity. In De Rerum Natura (The Mode Things Are), recounting the fifty-fifty earlier ideas of the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BCE), the Roman poet Lucretius (99-55 BCE) told the dramatic story of a turbulent primal earth that generated all forms of life, including behemothic humans, who would slowly come together to create social groupings. Lucretius was particularly concerned with the evolution of behavior about supernatural beings, which he viewed every bit anthropomorphic attempts to explain the natural world. In medieval Europe, Lucretius's ideas were largely forgotten in favor of the Christian account of homo origins in Genesis. Merely by the eighteenth century, philosophers proposed new, secular accounts that minimized the story of Genesis. In Scienza nuova (1744; The New Science), the Italian Giambattista Vico (1688-1744) proposed a theory of human origins that incorporated many of Lucretius's ideas, including the gigantic stature of early man, and he reiterated the anthropomorphic caption for the rise in beliefs about gods. Indeed, the start of Vico'south 141 axioms explains the importance of human self-projection equally a means of explaining the earth effectually them: "Past its nature, the human listen is indeterminate; hence, when man is sunk in ignorance, he makes himself the measure of the universe" (75).

Enlightenment philosophers similar Vico typically divided the evolution of human civilisation into three distinct stages. While his stages depended on the increasing composure of language over time, in De l'esprit des loix (1748; The Spirit of Police forces), the French political philosopher Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) used iii static stages defined less by fourth dimension than by geography and the effects of climate: savagery (hunting), barbarism (herding), and civilization. The French ideologue Marquis de Condorcet (1743-94) used ten stages, but he saw them as more dynamic than did Montesquieu. In Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'camaraderie humain (1795; Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind), Condorcet took a developmental view of social progress linked to the evolution of human reason over time. Condorcet was peculiarly significant to the thinking of Tylor'southward defining predecessor, the French philosopher of science Auguste Comte (1798-1857). Comte's Cours de philosophie positive (1830-42; Positive Philosophy) proposed three similarly dynamic stages premised on the growth of reason: the theological stage, dominated by superstition; the metaphysical, where spiritual thinking was replaced by political allegory; and the positivist phase of scientific reason. Comte's philosophy was popularized in United kingdom in 1853 by Harriet Martineau's condensed translation.

While Enlightenment thinkers and Comte referred to the development of "guild" or "civilization," the nineteenth-century German social philosopher Gustav Klemm (1802-67) used a novel term for his give-and-take of human evolution. In his Allgemeine Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit (1843-52; The Full general Cultural History of Mankind), he substituted the discussion Kultur for "society" (Williams 91). Still, Klemm, similar his predecessors, considered man civilisation or civilisation as a single condition. The exception was the German Romantic philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), whose unfinished Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (1784–91; Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Homo) insisted on cultural relativism, arguing that there was as well much variety to view all human societies as function of the same unilinear process.

Tylor'south method did not appear ex nihilo, then. He adopted Klemm's term, "culture," as preferable to "civilization." Virtually significantly, he used Comte's 3 stages wholesale, but he substituted Montesquieu's terminology of "savage," "barbarian," and "civilized" for Comte'due south ungainly "theological," "metaphysical," and "positivist." To these, he added a practical method for studying humanity, and this emphasis on scientific objectivity inside ethnographic practices differentiated his work from that of his predecessors. "Evolutionary Anthropology," as Tylor'south Victorian method was chosen, dominated British ethnography until the end of the nineteenth century. In his near influential piece of work, Primitive Culture, he spelled out two major contributions to anthropology: he defined culture clearly equally an object of report for the starting time time, and he described a systematic method for studying it.

His scientific discipline of culture had three essential premises: the being of 1 culture, its development through one progression, and humanity every bit united past one mind. Tylor saw culture every bit universal. In his view, all societies were essentially alike and capable of beingness ranked past their different levels of cultural advancement. As he explains in a later essay:

the institutions of man are as distinctly stratified as the earth on which he lives. They succeed each other in serial substantially compatible over the globe, contained of what seem the insufficiently superficial differences of race and linguistic communication, just shaped by similar man nature acting through successively inverse weather condition in cruel, barbarian, and civilized life. ("On a Method" 269)

The earliest stage of savagery featured largely in Tylor'due south study of culture; the term itself derives from the Latin for woods-dweller, and at the time information technology had both neutral and positive connotations as well as the negative ones that remain today. Societies within each stage take superficial differences masking their fundamental similarity, and the anthropologist's job is to identify the latter. Determining where the group stood on the hierarchical ladder of cultural development provided the context for interpreting all aspects of the society by comparison it with others on the same rung around the world. 1 of the most prominent consequences of this logic was the familiar practice in Victorian museums of displaying together all objects of one blazon from around the world, arranged to illustrate the intrinsic cultural development of a musical instrument, bowls, or spears, for example. A brief glance at most illustrated anthropological books from the time, such every bit Friedrich Ratzel'due south The History of Mankind (1885-86), demonstrates the same principle at piece of work.

The progression from savage to civilized did not occur evenly or at the same pace in every society, but the singled-out stages were always the aforementioned, much as the growth of the individual from infant to adolescent to adult takes a like grade in different places. The association this analogy created between primitives and children was roundly rejected in anthropology at the turn of the century, merely in the meantime it created a sense that Victorians were confronting their infant selves in what they regarded as archaic societies. In this sense, the scientific discipline of anthropology was not simply almost the written report of other, largely colonized people; information technology was also about the connexion between modernistic life in Europe and its ain earlier stages, and this meant that anthropology had much to teach the British most their own lodge. Tylor argues that elements of early civilisation continue on in subsequently stages as "survivals." Superstitions, plant nursery rhymes, or familiar expressions ("a pig in a poke") often are illogical and unintelligible. Such aspects of modern life, he argues, are survivals from mythology or rituals that served a purpose in the by simply had lost their meaning over time, even as the exercise itself connected. To Tylor, the most apparently insignificant aspects of Victorian life were critical to anthropology. Survivals were "landmarks in the course of civilisation. . . . On the force of these survivals, it becomes possible to declare that the civilization of the people they are observed amid must have been derived from an earlier state, in which the proper home and pregnant of these things are to establish; and thus collections of such facts are to exist worked as mines of celebrated knowledge" (Primitive Culture 1:71). Reuniting survivals with their lost meaning was the key to understanding the true nature of the primitive mind.

Ultimately, agreement the perceptions and working of that primitive mind was the object of anthropology. His key premise was the doctrine of psychic unity: the conventionalities that all humans are governed past the same mental and psychological processes and that, faced with similar circumstances, all volition reply similarly. The chief of psychic unity explained the appearance of identical myths and artifacts in widely disparate societies. While acknowledging two other possibilities—that each social club could have inherited the trait from a mutual ancestor, or that each came into contact with ane another at some point and learned it from the other—he argued that "independent invention" was the about frequent cause of such coincidences.

The defining trait of the primitive mind was its disability to remember abstractly. Because numbers are abstractions, counting was limited to the physical number of fingers or toes, for example, followed by "a lot." Language was nonexistent. For the same reason, primitives were unable to grouping like objects into abstract categories—all trees, or rocks, or flowers, for example. Instead, the archaic saw only individual copse, without understanding categories like a forest, because of their abstract nature. This was higher up all a concrete world, one in which each object had a unique identity or personality that could not be replaced by any other. Primitives were thus immersed in a world of singular objects. At the same fourth dimension they were unable to comprehend events, like thunder, in a logical way, considering they lacked the power to construct abstruse natural laws. Instead, primitives projected their emotions onto the world effectually them every bit a means of explaining natural events. In response to the threat posed by thunder, for example, the primitive invents an angry supernatural being to explicate it. When a tree ceases to bear fruit, the tree'due south spirit must be unhappy. Tylor chosen the archaic conventionalities in spirits "animism," a term that continues in employ today, and thus he follows a long tradition of imagining early humans as dominated by supernaturalism.

Similar Comte, Tylor held that the progress of culture was a slow replacement of this magical thinking with the power of reason. He produced a narrative of human development that begins with a global supernaturalism in the savage stage. Supernaturalism coexists with the development of language, laws, and institutions in the barbaric stage. In advanced civilizations, like Tylor's ain, reason and scientific thinking predominate. This is not a rational utopia, by any means. Magical thinking persists in the present; the primitive trend to imagine objects as having a life of their ain exists even inside the virtually civilized gentleman, who might think in a moment of frustration that a broken sentry was inhabited by an evil spirit. Tylor did non imagine modernistic culture in idealist terms, but, e'er the Victorian, he did view information technology as fundamentally better than that of archaic culture.

Evolutionary anthropology came under fire in the fin de siècle from within anthropology itself. There were numerous contributing factors, including a new emphasis on the importance of anthropologists doing their own fieldwork rather than examining the reports of others. But in terms of cultural theory, the most important criticism was that of the American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942). A German language immigrant to the Us, he was influenced by German Romantic philosophy, including Herder'south insistence on cultural particularity. In 1896, Boas published an influential critique of Tylor's science, "The Limitations of the Comparative Method of Anthropology," in which he persuasively challenged the basic notions of psychic unity and independent invention upon which Victorian evolutionary anthropology rested. Boas had been actively battling evolutionary orthodoxy since at least 1887, when he objected to the typological arrangement of ethnographic artifacts within American national museums, insisting that they should instead be displayed with other objects from their originating culture (Stocking, Shaping of American Anthropology 61-67). He argued throughout his work for cultural pluralism, for "cultures" in the plural, and with him began the terminal shift in anthropological thought from the traditional universalism to the new, particular theory of culture that characterized twentieth-century thought.

Evolutionary anthropology remerged in the twentieth century, as early as the 1930s simply more influentially later in the century, and information technology continues today. Unlike its Victorian variant, evolutionary thought now emphasizes multi-causality, the interaction of multiple events to account for the development of societies, as well as the presence of multiple paths in the development of particular cultures. In both of these regards, Tylor's central concepts of the compatible primitive mind, the single evolutionary path through 3 stages, and the universality of 1 human culture remain incomparably Victorian in their outlook, telling us more about the nineteenth century and its own civilisation, than they practice near contemporary anthropological idea.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published July 2012

Logan, Peter Melville. "On Civilisation: Edward B. Tylor'due south Primitive Civilisation, 1871." Co-operative: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add together your last date of access to Branch].

WORKS CITED

Boas, Franz. "The Limitations of the Comparative Method of Anthroplogy." Science iv (1896): 901-08. Impress.

Comte, Auguste. The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte. Trans. Harriet Martineau. Vol. 2. 2 vols. London: John Chapman, 1853. Print.

Stocking, George Due west. "Matthew Arnold, E. B. Tylor, and the Uses of Invention." Race, Culture and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology. New York: Free Press, 1968. 69-90. Impress.

—, ed. The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911: A Franz Boas Reader. New York: Bones, 1974. Impress.

—. Victorian Anthropology. New York: Free Press, 1987. Print.

Tylor, Edward B. "On a Method of Investigating the Development of Institutions; Applied to Laws of Marriage and Descent." Journal of the Anthropological Institute of United kingdom and Ireland xviii (1889): 245-72. Print.

—. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom. 2nd ed. 2 vols. London: John Murray, 1873. Print.

Vico, Giambattista. New Scientific discipline: Principles of the New Scientific discipline Apropos the Common Nature of Nations. Ed. Marsh, David. 3rd ed. London: Penguin, 1999. Print.

Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Civilization and Society. New York: Oxford Upward, 1983. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ESSAYS

Peter Melville Logan, "On Culture: Matthew Arnold's Culture and Anarchy, 1869″

Source: https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=peter-logan-on-culture-edward-b-tylors-primitive-culture-1871

0 Response to "Tylor 1871 Culture as ââåthat Complex Whole Which Includes Knowledge Belief Art Morals Law"

Post a Comment